Red Birds in a Tree: How a Rare Wildflower Became a Hummingbird Garden Star

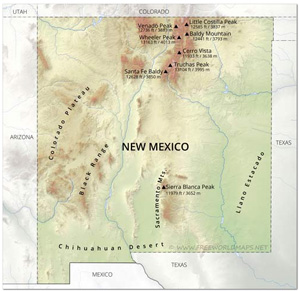

Red Birds in a Tree, known botanically as Scrophularia macrantha, is a cold-hardy, Wild West perennial only found in the rocky canyonlands and mountains of Southwest New Mexico. Agriculture, logging, mining, and ranching have dominated the region since the 1800s when Spanish and Anglo settlers staked a claim to its Apache ancestral lands.

Early October is the approximate end of bloom time for this hummingbird favorite. Its cheerful, true red blossoms perch on tall spikes that rise up from mid-green foliage remarkable only for the leaves’ sharply serrated edges. In a woodland setting, you might pass it by without a second glance if not for the flowers. But standing alone, rooted amid a rockfall it also likely would command attention.

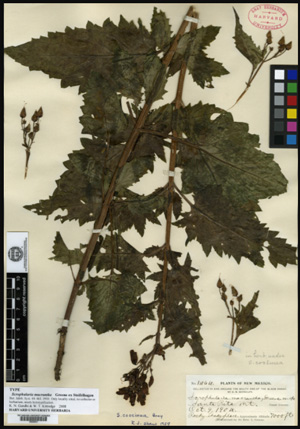

Perhaps it was the plant’s tenacity amid rocks or its bright red flowers that caught the eye of another Southwest New Mexico native — botanist Orrick Baylor Metcalfe (1879 – 1936), who is usually referred to as O.B. Metcalfe. Or perhaps Metcalfe glimpsed hummingbirds hovering around the herbaceous perennial. Late summer through mid-October is a busy time for southward hummingbird migration in the region’s mountains, and Metcalfe collected specimens of the wildflower’s blossoms and foliage on October 9, 1904.

A Kneeling Nun Called Santa Rita

Metcalfe found S. macrantha at an altitude of 7,000 feet on Santa Rita Mountain in the Santa Rita Mountain chain, which is small enough to not appear on maps. New Mexico’s Santa Ritas are part of the Mimbres Mountains, which, in turn, are within the nearly 560,000-acre Black Range running north-south on the east side of the Gila National Forest. The U.S. Forest Service reports that a few locations in this area are the plant’s only native habitat, including the talus (tumbled rock) slopes of a steep, volcanic monolith named the Kneeling Nun.

The New Mexico Rare Plant List says S. macrantha is also at home in piñon-juniper woodlands, mountain coniferous forests, and “occasionally” at the bottom of canyons.

The Kneeling Nun, which is about 15 miles east of Silver City, may possibly be what Metcalfe called Santa Rita Mountain. Accounts about the Kneeling Nun sometimes call it a mountain, and Spanish folktales from the area have referred to it as Santa Rita.

A limited distribution range can cause a plant to be rare; factors threatening its survival increase the rarity. Scrophularia macrantha is on the New Mexico Rare Plant List, which is published by a consortium of entities including the New Mexico Natural Heritage Program. The organization identifies the perennial as being threatened by mining, quarrying, wildfires and fire suppression. This doesn’t mean that S. macrantha meets federal standards for being considered endangered (at risk of extinction) under the Endangered Species Act, but its conservation needs to improve.

One of the world’s largest open pit copper mines is close to the Kneeling Nun. The mining town of Santa Rita once existed near the monolith. However, by the 1950s, the town disappeared due to excavation expanding the mine variously known as the Chino, Santa Rita, and Santa Rita del Cobre (copper) mine.

The Kneeling Nun and what is now known as the Santa Rita Mining Area are located in Grant County. Just to the east in Luna County is Cookes Peake in another section of the Mimbres Mountains. It’s also a longtime mining area and another location that the USFS cites as home to S. macrantha.

Cookes Peak (also sometimes spelled Cooke’s or Cooks) is likely the area where Denver Botanic Gardens Curator Panayoti Kelaidis discovered a single S. macrantha plant in 1992. He found it by chance as he and his brother-in-law, Allan Taylor, sought Arizona Cypress.

Being careful not to harm the S. scrophularia, Kelaidis gathered “a pinch of seed.” He gave part of this treasure to the UK’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, as well friends, including New Mexico horticulturist David Salmon. Kelaidis credits Salmon as being “the first to successfully grow and market” S. macrantha and the person who gave it the common name Red Birds in a Tree. By 2008, Red Birds was being championed by Plant Select, a nonprofit consortium that focuses on drought tolerant plants and includes Denver Botanic Gardens and Colorado State University.

Botanical alliances, such as Plant Select, help worthwhile but less known plants find their way into people’s gardens. Herbaria, including the New Mexico Consortium (NMC) of New Mexico State University, are another kind of alliance. They ensure the survival and study of plants.

Building a Territorial Collection

From 1901 through 1905, Metcalfe collected for the Agricultural Experiment Station of the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (now New Mexico State University, Las Cruces). By October 1904, he was either completing or had just earned his Master of Science degree from the college. Two years earlier, he had completed his Bachelor of Science degree there.

Metcalfe’s mentor, botanist Elmer Ottis Wooton (1865-1945) began developing the college’s herbarium in 1890. Wooton’s goal was to create a comprehensive collection of southern New Mexico territorial plants (statehood didn’t occur until 1912) and to share specimens with herbaria nationwide and abroad.

Botanical collecting requires fast work, an eye for the unusual, and acceptance of the fact that you may not earn much. For example, whether to make money for himself or the college, Metcalfe sent a letter to Kew Gardens in November 1904 offering to sell them a set of 450 New Mexico specimens he collected for 8.5 cents each.

Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries

We don’t know whether S. macrantha was one of the specimens or Kew made the purchase. However, Harvard University’s Gray Herbarium alone possesses hundreds of Metcalfe specimens representing 76 plant families. These include Metcalfe’s most important example of S. macrantha — the “type” specimen that he sent to botanist and clergyman Edward Lee Greene (1843 – 1915) who analyzed it to establish the plant’s characteristics and scientific name. Greene was an expert on flora in Southwest New Mexico having botanized there from the late 1870s through the early 1880s.

An Academic Faux Pas

Establishing a botanical name for a plant is an expensive process that concludes with publication of its title and description, usually in a scholarly journal. But Greene never completed the process for S. macrantha. Instead, German botanist Heinz Stiefelhagen accidentally beat him to it.

In 1910, Stiefelhagen completed a study about the distribution of the Scrophularia genus worldwide and submitted it to the journal Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik. He included Greene’s description of S. macrantha and mistakenly gave the western botanist credit for formally publishing the name. So, when Stiefelhagen’s study appeared that year, he technically performed publication. That's why the plant's full botanical name is Scrophularia macrantha Greene ex. Stiefelh.

We owe the information about this academic faux pas to Bureau of Land Management botanist, Patrick Alexander, who encountered it as notes scribbled on a duplicate (isotype) specimen sheet of S. macrantha that the NMC had lent to the University of California, Berkeley. Like Metcalfe, Alexander is a graduate of NMSU and collected for the school’s herbarium. He also served as a curator.

Patrick Alexander

Returning to the issue of ecological threat: Alexander’s 2010 photos of S. macrantha growing wild in the Black Range’s Railroad Canyon make it obvious what beauty could be lost if the plant takes too many hits from natural disasters or conservation failure. Three years after Alexander recorded the images, a devastating wildfire swept through Railroad Canyon.

A Figwort by Another, Prettier Name

The Scrophularia genus is part of what used to be called the snapdragon family, but now is known as the figwort family (Scrophulariaceae). In 1998, DNA testing caused snapdragons to move to the plantain family (Plantaginaceae), which is where penstemons reside but not plantain bananas (plant naming can drive one bananas!).

Although figworts are luscious sources of nectar, their flowers aren’t known for being showy or attracting the human eye. Of course, that isn’t the case with S. macrantha, which was commonly referred to as Mimbres Figwort until gaining the prettier name of Red Birds in a Tree. Bees love many figworts, but the New Mexico Rare Plants List notes that this one is only pollinated by hummingbirds.

Mimbres Figwort is a useful moniker because it identifies the general area where S. macrantha can be found in the wild. As already mentioned, it’s native only to the Mimbres area. Fortunately, it’s adaptable to places ranging from mild coastal environments to high plains areas where summers are hot and dry and where winters are freezing cold.

Sun Loving and Drought Resistant

Red Birds in a Tree needs full sun to thrive, which means planting it in a location with direct sunshine for at least six hours a day. It’s an especially good choice for dry climates because it’s drought resistant once the roots are established.

Establishing the roots usually requires daily watering for about a month to help them extend into surrounding soil. Then you may be able to cut back to watering every other day. A lot depends on the frequency and intensity of rainfall from spring through summer in your locale.

Even after Red Birds is well established — such as in its second season — supplemental watering is necessary to help it look its best. But similar to most Salvias, this species isn’t meant for soggy soils. Remember that the soil in its native habitat contains plentiful, well-draining grit. Adding some fine gravel along with organic matter to your planting site will improve drainage.

You can expect Red Birds to grow up to four feet tall and two feet wide. As to companion plants, pair it with waterwise choices like Agastache and many kinds of drought-resistant Salvia.

At Flowers by the Sea Farm, we regularly hear from those of you who are wildlife gardeners concerning what plants are best for attracting hummingbirds. Based on customer advice and our own experience growing Red Birds, we decided to add it to our online catalog in 2021 just 117 years after Metcalfe snipped its foliage for specimen sheets.

Metcalfe & His Mother Mountains

Let us now puzzle over the less-than-famous botanist who decided that Mimbres Figwort deserved a botanical name. But to do so requires a bit of family history.

O.B. Metcalfe’s father was James Keith Metcalfe (1824 – 1910), whose last name is sometimes spelled “Metcalf” like the Eastern Arizona mining town connected to their family history. James and his brother, Robert, were miners as well as ranchers.

Around 1870, the two brothers homesteaded northwest of Silver City near the Arizona border in what eventually became known as the Mangas Valley. The area gained its name as the birthplace of Eastern Chiricahua Apache chief Dasoda-hae (1795? – 1863) who the Spanish called Mangas Coloradas (Red Sleeves). Another reason for the valley’s name was James and Robert dubbing their homestead — tens of thousands of acres of dry grazing land, mountains, and creeks — the Mangas Ranch.

It’s a mystery as to why there seem to be no field notes or writings by O.B. Metcalfe — at least none accessible online or through archives. It also seems odd that so little has been written about him considering that he was a member of one of Southwestern New Mexico’s prominent pioneer families and the NMC Herbarium calls him one of the region’s “renowned botanists.”

Another mystery concerns why Metcalfe didn’t work as a botanist after graduation. Instead, at some point, he taught auto mechanics at his alma mater.

Sometime between 1906 and 1908, Metcalfe married Pearl Lucinda Parks (1885 – 1987), who he may have met when she was teaching elementary school in Santa Rita. Together, they ran a bee business on a farm in the Las Cruces-area town of Old Mesilla.

In 1916, O.B. and Pearl moved with their four children to Mangas Ranch. They relocated again around 1919 to Silver City where they established an auto dealership. But the Great Depression killed their business, caused them to lose part of Mangas Ranch, and led to the death (1934) of their son, Frank, and of O.B. (1936) while working in the area’s Pinos Altos Gold Mine.

O.B. Metcalfe was the youngest of five children. His mother, Sarah Shackleford Metcalfe (1839 – 1885), died when he was 6 years old, and that must have been tough on him. Based on his poem “To the Mountains,” which he published in the Boy Scout magazine Recreation in April 1905 (Vol, 22, page 263), Metcalfe found a mothering solace in the mountains of Southwest New Mexico.

To the Mountains

By Orrick Baylor Metcalfe

I’m sick of heart, I’m sad to-day,

This city life is not my way.

Where man meets man, they harbor strife;

Give back my boyhood mountain life.

Oh mother, land where I was born!

Where I was free from strife and scorn.

Oh mother mine of jagged arms!

Take back your child from human harms.

Why was Metcalfe so sad at age 26 and feeling harmed by life in Las Cruces? One can only guess. With the exception of the poem and his letter to Kew Gardens, the botanist’s words seem to be lost to the mists of time. Fortunately, his brief horticultural legacy is not. Neither are the vibrant flowers of Scrophularia macrantha as long as we make room for them in our gardens.

Questions About FBTS Plants

Obviously, our Everything Salvias Blog isn’t solely about sages. We grow many plants — such as Red Birds in a Tree — that are great companions for Salvias. Please feel free to contact us if you have questions about any of our stock. We’re always glad to hear from you and share what we know.

2 Comments